Into The Unknown

I’ve been living alongside grief for a while: the deaths of two good friends, a friend’s divorce after decades of marriage, my father’s cancer, and the inevitable effects of living with my own autoimmune disease. Some days feel almost normal. Some days I can barely get out of bed.

But it is the end of March, and the snow is gone. The clocks have been changed, the first thunderstorms of spring have crashed their way through. The hazelnuts, the first trees to bloom in my woods, have sent their pollen on the wind. The Virginia pennywort, the first wildflower to break through the earth in my woods, has pushed up green leaves.

Now, the redbud trees are full of tightly closed, bright pink buds. The cutleaf toothwort is blooming, along with dandelions and the first wild violets. Yesterday a wren was singing what sounded to me like a springtime song.

As the country changes shape around us, as friends move through their own personal hurts and sorrows, as my chronic illness symptoms flare and fade and flare again, I find ways of moving through pain and grief. In watching the woods come alive again, certainly. And also in making artwork.

In 2018, I was living my best, most active life. Hiking miles daily, photographing nature and sharing it on social media, working (more than) full time as an artist. Participating in art fairs, stocking gift shops and galleries, volunteering for committees and projects in my community. Then I began to have strange symptoms.

One after another, unexplained sensations appeared in my body. Neurological, gastrointestinal – even my balance seemed to be messing with me. Odd combinations of things became difficult: both hiking and grocery shopping made my leg muscles spasm and left me exhausted. Both riding in a car and house cleaning tightened my chest muscles and made it difficult to fully inhale. Machine sewing and reading both gave me motion sickness. Many days simply showering would consume all my energy.

By 2020, when Covid was shutting down the world anyway, I was no longer able to handle the long hours of art fairs or the extended studio time needed to stock gift shops and galleries. In the small amount of time I was able to get in the studio, I began playing with some ways of making that were more suited to my newly ill body.

I couldn’t hike in the woods much anymore, but I learned how to bring leaves from the woods inside and use them to eco-dye papers (which I had a lot of – left over from the bookbinding my body would no longer let me do). The method I used (steaming bundles of paper and leaves) left abstract marks and colors on the papers, which became a bit torn and crumpled in the steam pot, slightly damaged but still beautiful. I dyed sheet after sheet of paper, and they accumulated around me in my studio.

Then I started to hand embroider into the dyed paper. I’m getting ahead of myself, but timelines like these are rarely linear, and so many things are moving and changing at once that it can be difficult to assign cause and effect.

I remember the first embroidery I ever made. I was probably 9 years old, living in a tiny Indiana town carved out of cornfields. There wasn’t much – a DQ, a post office where I bought single stamps and pasted them into albums, a small library, and a Kmart, which had a small craft department.

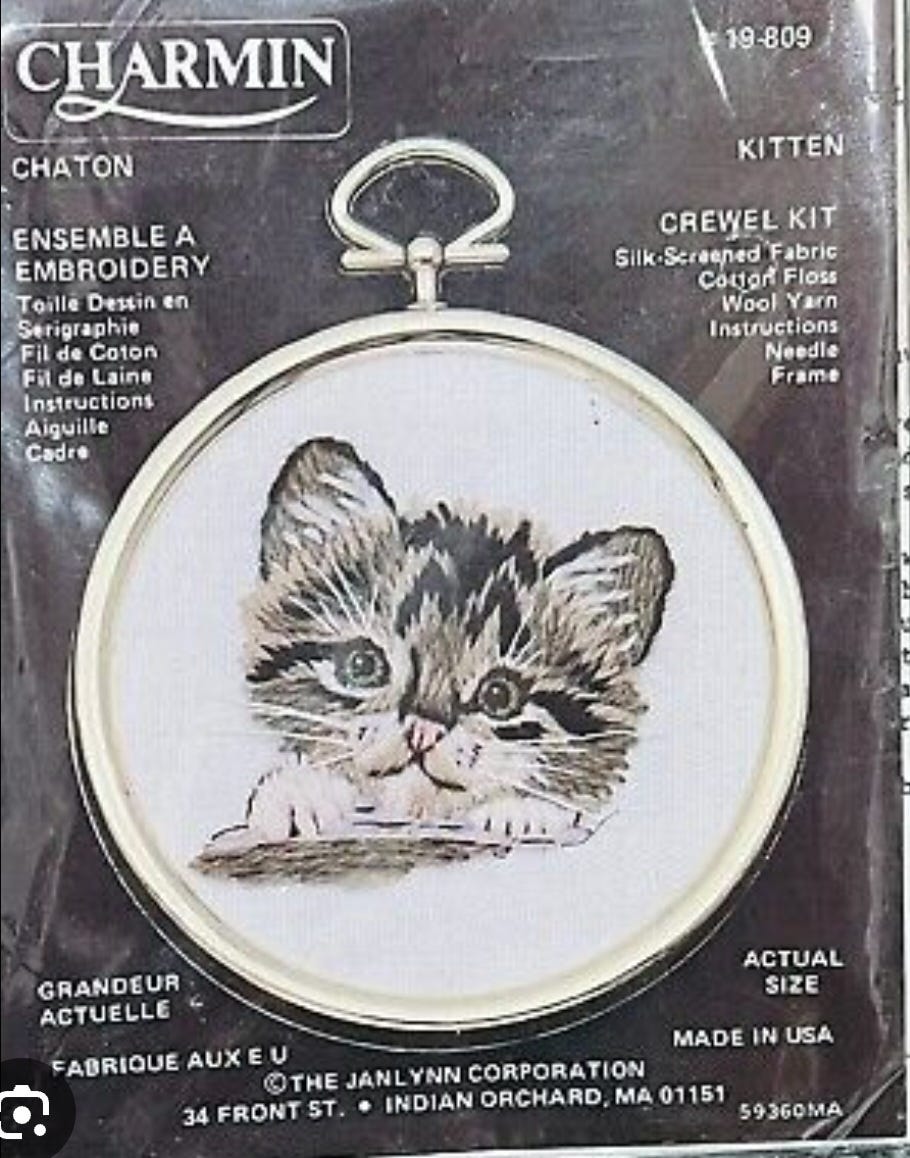

No one I knew embroidered, so I can’t to this day explain why it attracted me – but I spent my allowance money on a tiny kitten embroidery kit, complete with instructions, threads and needles and a tacky silver frame. I remember trying to decipher the stitches from the small, folded direction sheet. I wish I still had this embroidery – who knows where it disappeared to along the way. I’m sure it wasn’t skillfully executed, but I loved it and hung it on my bedroom wall. I moved on to cross stitch kits, and by high school I was designing my own cross stitch patterns using colored pencils and graph paper.

I never really stopped embroidering by hand, even through engineering school, when I barely had anything like free time. But I never incorporated it into my art practice. Unlike machine sewing, it’s too slow to allow for building inventory for art fairs and gift shops.

Back to 2020, when the world stopped briefly and my body was changing with illness day by day. Slow work seemed just the thing to help me navigate and survive (See here my essay on doodling with stitching and hand sewing’s health benefits).

I took one of the papers I had eco-dyed and began to stitch into it by hand. Where the paper was torn, I mended it with stitches. Where there were holes, I accentuated them with stitches. I burned holes in the paper with a soldering iron and edged the holes with stitching. There was no plan, except the one laid out by the accident of the paper. And through much of it, though I can’t explain why, I cried.

I was overwhelmed with grief and fears, some Covid-related and some personal. Both the world and my body had become scary places, filled with pain and uncertainty and loss. But hand stitching, somehow, made it all seem okay.

At the same time that I was re-engaging with embroidery, I was also just beginning to forage vines and branches from the woods and bring them into the studio. I was especially interested in utilizing the invasive vines that I was removing from my woods. While taking a wonderful online basket-making class from Harriet Goodall at Fibre Arts Take Two, I experimented with twisting some invasive bittersweet vine into three-dimensional structures.

Then three things came together for me: I had samples and pieces of eco-dyed paper that I had embroidered; I had several vine frameworks I had twined; and I had lots of waxed linen thread left over from years of hand binding hundreds of blank journals for gift shops and art fairs (Book binding is harder on the body than you might realize. My body was no longer capable.) I cut some of the eco-dyed paper to fit an open section of a vine framework. I hand embroidered into the small paper shape. Then I used the waxed linen thread and a modified bookbinding stitch to mount the embroidered paper to the framework. It felt good. It felt right.

So I kept on, not knowing exactly what I was doing or why, until I’d filled most of the open spaces on the framework with tiny paper “quilts.” Then, on a whim, and using fine sewing thread, I used a technique called looping, or knotless netting, to fill an open section, creating a delicate, uneven web.

When I was finished, I named the piece How Grief Moves Through the Heart – because that’s what it felt like had happened. I cried a lot while making the piece, and I can’t explain, even now, why making the work was so cathartic.

In retrospect, I can mark it as a turning point in my art practice and the kind of work I was making. The work became more personal, more emotionally important to me. Sometimes in the midst of things, it can be hard to see what we’re doing, and it is only in looking back that we can understand. These new materials and methods require letting go of expectations and allowing uncertainty into my work, mirroring the uncertainty that illness has created in my life. It’s natural for this new work to explore the subjects of illness and grief.

A Diagnosis

The second piece of artwork I made on this journey was more deliberately about my grief and anxiety. By this time, I had a diagnosis – Scleroderma, a rare autoimmune disease – but not much relief from symptoms and no idea how to live within the limits of this body.

I was newly introduced to the concept of pacing, a self-management strategy which involves balancing activity and rest to manage chronic illness symptoms by learning to act within energy limits. I missed binding books – what if I made a book little by little over time, by binding just one book signature (section of book pages folded together) per day?

Around that time, I went on a field trip to the local scrapyard with two artist friends. We wore our boots and leather gloves and we poked our way around piles of metal junk, choosing things that spoke to us. When I looked at one piece of rusted metal, bent and deformed and no longer useful for its original purpose, it reminded me of grief, of anger, of loss, of anxiety – and I thought I might find a way to affix my own emotions to its structure, to use it as an armature for my own volatile feelings about having Scleroderma and the limitations it places on my body and my life.

I tore some of my eco-dyed papers to size and folded them into small eight-page book signatures. Then, almost daily, I did automatic writing on one of these small signatures, purging myself of negative emotions, my hand moving as fast as my mind was going, so the final writing is – thankfully – illegible.

Handwriting bears witness to the body, uses the body, demands of the body, taxes the body. The point is not to ever go back and read this journal, or to have anyone else read it, but to rid myself of the emotions, to channel them into another vessel. I bound each of the signatures individually to the rusted and bent metal piece using waxed linen thread and a modified Coptic binding stitch.

Returning to the piece almost daily for nearly a year, the piece grew slowly, slowly – literally converting grief and anxiety and loss into artwork, signature by signature, joining my difficult emotions to strange beauty – or if not beauty, exactly, then a kind of grace and movement.

What does it mean to work on something for an extended period of time? Time itself becomes a raw material in the work. The time spent making this piece is the whole point, really. The catharsis is in the writing itself, in the making, in the alchemy of converting emotions into something material, something apart from myself that I can examine and observe. The making is the artwork, and the final piece is really an artifact of that time spent making.

Being Chronically Ill

I am an autodidact, self-trained in sewing and an amateur naturalist. Chronically ill people are often forced to be autodidacts, and when your disease is rare, you may know more about your illness than your doctors. But there is a downside. For me, it has become obsessive and exhausting, researching symptoms, possible diagnoses and treatments.

In my next eco-dyeing session, I experimented with dyeing pages torn from Gray’s Anatomy, especially pages that discussed parts of the body affected by my disease – the skin, the digestive tract, the muscles, hips, and shoulders.

After eco-dying the pages with leaves, I layered them with fabric and machine quilted, obliterating the text of Gray’s Anatomy, and it felt good – sometimes all the medical information is so overwhelming. The tiny quilts were cut to fit open spaces in a framework of invasive honeysuckle vines, then hand embroidered.

In one section, I made a print from the top of a pill bottle using acrylic paint (the medications can also be overwhelming) and responded with French knots to the mark made.

In the remaining open sections, rather than loop with thread like in the previous work, I wanted something denser, more solid. I had been making handmade paper cordage from leftover bookbinding paper, and I had some cotton string I had eco-dyed along with the papers. I used these to create hand weavings in the open sections of the frameworks, then extended the hand embroidery into the weavings to unify everything.

When Knowledge Doesn’t Feel Like Power is dense with stitching and weaving, and dense with meaning for me. It reflects how I feel about the overwhelming information I have to sort through to get answers. The piece is both abstract and figurative, a record of my symptoms and an attempt to overcome them.

I found my way into working with eco-dyed papers and hand embroidery intuitively, even accidentally. But working this way has been more emotionally laden than I could have expected, and more cathartic. There are metaphors here I didn’t even intend at the time of making. The small intuitive paper quilts are like fragile skins, like maps to unknown places, like the shapes of cells and antibodies under the microscope. The webs created through looping are delicate and messy, yet dimensionally stable. They have holes and ragged spots. Yet they remain structurally sound and have their own strange beauty, like old cobwebs in nature but also like my tangled emotions, my struggle to come to terms with my illness and remain intact.

If you want to see more of my work, you can visit my website: www.michelepollock.com

What a beautiful way to deal with chronic illness! Your piece really moved me. I love your art and creativity. I have a good friend who has been living with scleroderma almost 50 years. During that time she got her PhD, ran a large department in a hospital, and religiously traveled all the while dealing with the constant changes in her body. Now, at 70 she still travels (only to warm places and with some help) and is a good friend to many. She’s been a huge inspiration to me when I indulge in self pity as in how to deal with life’s challenges.

I love how you are using your art and creativity to move you forward and to be a healing and positive influence on those around you. Thank you so much for sharing this!!

Oh, your work is absolutely stunning! I clicked on this post because of the title. Last year I had trauma surgery for a broken back and was subsequently diagnosed with stage 4 metastatic breast cancer to the spine. I have extensive nerve damage in my legs and feet from the broken back, and my brain gets cotton-headed from the cancer treatment.

My knitting projects were just too involved for me to stick with, but I’m a “maker” so I had to do something. Then I discovered watercolor, and I believe it’s partially responsible for saving me. Creating every day keeps my brain and body occupied and looking forward to tomorrow.